It’s hard to believe I’m now five years older than my friend Ellen Meloy when she died, though she was ten years older than me when alive. And even harder to believe she’d be 73 now. That’s one thing about dying young: so you are forever. She was thin, and tall, and gangly, with haywire red hair and goofy front teeth which she exploited for her own humor. She was a caricature of herself, and always the butt of her own jokes–always the straight-faced wit.

Before I knew her well, I had to study her closely after she said something I found hilarious, as I, forever in awe, didn’t want to guffaw if she was serious. I usually found her staring off at clouds, eyebrows raised, innocent of any implication. After knowing her longer, I dispensed with checking, and just burst out laughing, knowing whether she showed it or not, she was too.

When she died at 58, I remember thinking it was her way of getting the last laugh; that she was out there, just ahead of us on the trail, unseen, around the next bend, just out of sight, laughing at how we hadn’t gotten the joke.

It’s our great fortune that the good folks at KUER’s RadioWest recently uncovered a collection of essays Ellen wrote and read for NPR between 1994 and 1998. They partnered with Torrey House Press to publish them; the book is called Seasons: Desert Sketches by Ellen Meloy and will be published in April 2019. To buy it, click the Torrey House Press link above; to listen to Ellen read an essay, click here.

Here’s an article I wrote on Bluff, Utah and Ellen for the now defunct Wasatch Journal in 2009.

The Cosmic Nexus of Bluff, Utah

And the Woman Who Wrote It

Bluff, Utah. From a car hurling down Bluff’s main street, the two-lane SR191, a blink-of-an-eye tour reveals the San Juan River’s tamarisk-choked floodplain; Butler Wash’s wide, torrent-scoured arroyo; the pioneer-stopping Bluff Sandstone cliffs; and tumbleweed on course for Iowa. In town, dusty rutted sideroads struggle to maintain their Mormon-gird dignity while skirting mud wallows large enough to swallow a Hummer, and still provide access to an assembledge of dwellings perhaps best described as eclectic-historic chic. Bluff is funky and backwoods creative, or maybe desert-rat eccentric. In any words, Bluff is a sight to see.

Bluff is a pocket whirled into cliffs by dust devils, where unfurling winds dispense an indiscriminate accumulation. Empty wooden storefronts, the fading red of protracted sun exposure, and vintage trailer parks front the highway near a new timber-sided megahotel. Under ancient, breezy cottonwoods a beautiful, aged, handhewn-stone gas station stands abandoned and quite removed from the busiest place in town, the metalic quickmart that serves as grocery, gas station, and central communication network for Bluff and its multi-hundred square-mile, near roadless exburb.

Although Bluff is also home to a wonderful, if unconventional, restaurant or two; miscellaneous poets, sculptors, and painters; a bona fide coffee shop; some of the most beautiful sandstone-block Victorian homes in Utah, and the increasingly rare roadside stretch of junkyard sculpture, it’s the not the kind of place you’d expect to harbor a Pulitzer-prize finalist; a yearly arts festival drawing the likes of Terry Tempest Williams; or a fund encouraging desert literature, but there you have it.

About 250 people claim to live in Bluff these days. And although founded in 1880 by the Latter Day Saints’ famous Hole in the Rock Expedition (whose mission was to protect this remote quarter from invading gentiles with their cows and immoralities), it is now better known as the put-in for San Juan River trips. Latter Day Saints and river runners invaded the place in the last century—it was water that drew everyone here in the first place—making for an adventurous mix of caffeine-shunning rancher-Mormons; mocha-sipping, self-proclaimed misfits; holdover cowboys; Athabaskan-speaking Diné; missionary Episcopalians; erstwhile artistes and moon-eyed tourists all regarding each other suspiciously while doing the wash down to the Cottonwood Laundromat. Bluff’s slogan, “Whatever the Great Southwest is to you, you’ll find it ALL in BLUFF,” is alarmingly accurate. Bluff could be the accrued answers to a cosmic-scale free-association quiz.

You might be wondering why anyone would set roots here if they weren’t born to it, or for that matter, do anything but hit the accelerator on a drive-through, but, you see, that’s Bluff’s mesmeric charm. Amidst the seemingly endless miles of tawny, cliff-edged desert, Bluff serves as portal—not only to the desert’s ancient imagination, but to our own. A walk in any direction earns the San Juan River’s soothing waters, the Bluff Sandstone’s wind-carved hoodoos, and glimpses of prehistoric dwellings where rock art still radiates enigmatic messages. A daily seat under a lone pinon atop a sandstone ridge has been known to inspire more than one prize-winning book. In the world’s abundance of perfect, magazine-spread landscaping and arbitrated adventure travel, Bluff’s surrounding desert, with its unnumbered canyons, golden mesas, hidden springs, rescue-less dangers, and even its accidental distinctiveness is beginning to match roadside sculpture in rarity.

Ann Walka, a poet who splits her time between Flagstaff, Arizona and Bluff, says “There is a sense of endless space here, and the quiet spills from the canyons right into town. What people notice is so much more connected to the earth. Meeting on the road, people talk about last night’s moon or the neighbor’s hollyhocks. Bluff is a place where you have a sense of belonging and of privacy.”

Spectacular and idiosyncratic, Bluff’s sense of place is difficult to capture in words; luckily it was home to someone who wanted to spend a lifetime trying. If you want to experience Bluff’s enigmatic nature without the long drive, read Ellen Meloy. Perhaps best known as a Pulitzer Prize finalist for her book, The Anthropology of Turquoise; Meditations on Landscape, Art, and Spirit, Ellen moved to Bluff with her river-ranger husband in 1995. It was Bluff’s paradoxes that drew her: access to the nearby faraway, the desert’s striped-clean calm and blistering passion, its endless adventure and small embraces, the close community of “exibitionist hermits.” And Ellen fit right in. Tall, slender, her mind-of-its-own red-blond hair awhirl on the slightest breeze, her sun-baked skin glowed the color of redrock. Following those long, brown legs up a steep canyon from the San Juan River was a trot for anyone altitudinally-challenged. But even at her strong pace Ellen noticed the faintest pink blush of Indian paintbrush in bloom; spied the perfectly cryptic, thumbnail-sized baby toad popping away from moving feet. She knew the exact shade of the sky that day, turquoise not azure; summer’s intense light burned “the color of a sparkler’s core.” Ellen’s observations were always specific—detailed, accurate vignettes of this particular desert—her books’ language matched her brain’s precision and called a distinct vision of Bluff and her home desert into being.

Ellen wrote, “The San Juan River flows by my home and is so familiar, it is more bloodstream than place. Everything about it is tangible—a slick ribbon of jade silk between sienna canyon walls hung solid against a cerulean sky, pale sandy beaches, banks thick with lacy green tamarisk fronds, in which perch tiny gold finches.”

Ellen’s precise language had the unexpected effect of sending the reader not only from armchair to a full-body river dunking, but from specific to universal. Ellen evoked a deeper understanding, an echoing memory of an unfathomable connection we share with all that is not human, the pull that calls us still to places like Bluff. It may not seem many people would be fascinated with the intricacies of this remote landscape’s esoteric workings, but Ellen’s enthrallment and love burned from the page. She was able to speak openly about her sensual intoxication with this place, and by so doing evoke in others similar reactions. In her book, Eating Stone; Imagination and Loss of the Wild, Ellen writes, “Behind a gravel bar, a dense grove of tamarisk has turned the color of ripe peaches. An ellipse of pale rose sand lines the inside of a river bend of such beauty, you could set yourself on fire with the rapture of that curve. In it lies a kind of music in stone that might cure all emptiness.”

Imagine a beauty that could cure all emptiness. An impossible vision? Many find such a place on a slow meander through this landscape’s austere profusion. Melding into Bluff’s lonely quarter on an inflatable raft’s summer-warmed pontoon, your only responsibility to watch clouds morph indigo sky. Flat water’s languid current swirls the raft in gentle arcs as you trail fingers in water the color of liquid rock. As you drift by, cliffs seem to unroll, echoing wavelet lappings and reflecting water’s glitter in shaded overhangs. Or mold your body to a slickrock curve, hide from shoulder-slumping heat in cold-rock relief, nap, sleep, and dream of the lion curled here last night. Feel his full-bellied paddings as, across the river, he watches you now.

But, remember too, Bluff and it’s encompassing landscape is not Eden; it is instead quite real. There can be hardship here. Ellen’s book, The Last Cheater’s Waltz: Beauty and Violence in the Desert Southwest, details her realization that the stunning landscape of her own backyard is a deadly “geography of consequence.” Amid uranium tailings, missile ranges, and atomic test sites Ellen charts her “deep map of place,” contemplating a topography “where an act of creation can mean the complete absence of life.” This writer’s skill was complete, making us both desert esthete and activist.

Ellen’s sudden and unexpected death in 2004 caught her friends completely off guard. It was as if she slipped around some desert bend laughing, while our eyes were blinded by the sun. In the days following her death, many said, “o.k., Ellen, enough of the joke. You can come out now.” But Ellen, always a trickster coyote, didn’t respond. Ann Walka begins her lovely poem about Ellen with the line, “And for her next trick…” Somehow this death at home, centered on her personal map, suddenly and without fanfare, was very Ellen and very Bluff.

In Ellen’s remembrance and tribute to the place she and so many loved, friends and family created The Ellen Meloy Desert Writers Fund to encourage writing that combines an engaging individual voice, literary sensibility, imagination and intellectual rigor to create new perspectives and deeper meanings in desert literature. The Fund offers a yearly $2,000 award (now $5000) to an individual of similar passion and desire to go to their desert and write.

Although only in existence three years (since 2006), the Fund has provided much needed recognition for desert literacy, and sent two writers into the desert to scribe their own specifics of place. Rebecca Lawton of Sonoma County, California, the first Meloy Award winner, will continue our understanding of Utah’s many incarnations with her project Oil and Water. Lawton writes, “The Uintah Basin, home for millennia to people with wildly different views, still draws those of diverse descent and interests…Over time, everyone from ancient Puebloans to modern agriculturalists has lived on the Green River’s banks. Oil and Water will contrast attitudes toward this harsh but compelling place while bearing witness to demands each lifestyle places on the basin’s limited resources. The land will give testimony to those who inhabit it.”

The Award’s second winner hopes to capture an unwritten desert, replete with its own beauty and peril. Lily Mabura, currently of Columbia, Missouri, plans to travel to the Chalbi Desert and Lake Turkana in the North Eastern Province of Kenya, a region known locally as World’s End to write about the region’s nomadic ethnic groups and arid landscapes. Lily says, “It is difficult to travel to this region of Kenya due to extreme terrain and banditry or militia incursions from Ethiopia and Sudan. One must wait for armed convoys for escort…Like most Kenyans, I am petrified by the region, but there is the writer in me who really wants to see it and, gradually, my curiosity has eclipsed my fears, even though I suspect my real test is yet to come. I am hoping that my experience and the stories that emerge from it will enlighten others about this region, which deserves more attention in terms of humanitarian aid, education, security, environmental conservation and infrastructure.”

What these writers seek and what the Desert Writers Fund hopes to provide is what Ellen sought and found in Bluff’s abundance. Ellen wanted redrock and solitude, home and community. On her daily rounds she traversed river and canyon, garden and loving relationships, weaving everything into her own narrative of life and land, home and family. Ellen’s address and kin included slickrock and wandering bighorn, boiled lizards and the “brazen harlotry” of the desert in startling bloom. Ellen knew narrow slickrock canyons to be the halls of her own home, mule deer as neighbors, and the muddy San Juan as provider. She felt—and desperately wanted to communicate—the human use and abuse of nature was as dangerous as sawing off the limb on which we sit. If we soil the ground with atomic fallout, she said, decimate the bighorn’s last stronghold, dam the last rivers—we damn ourselves.

Perhaps Bluff’s significance, its message, is that regardless of our back-of-the-hand-on-forehead human tribulations and dreadfully significant problems, unexpected, funky, irresponsible, glorious possibility exists by the bucketload, and beauty—healing, transformative beauty—still lives in the world. Go, create some junkyard sculpture; go, lie in the desert and dream yourself awake.

In Ellen’s Words

One morning in a rough-hewn, single-room screenhouse, in a cottonwood grove but a few wingbeats beyond the San Juan River, I poured scalding water through a paper coffee filter into a mug that, unbeknownst to me, contained a lizard still dormant from the cool night. I boiled the lizard alive. As I removed the filter and leaned over the cup to take a sip, its body floated to the surface, ghostly and inflated in mahogany water, its belly the pale blue of heartbreak.

I sat on the front step of the screenhouse with sunrise burning crimson on the sandstone cliffs above the river and a boiled reptile in my cup. I knew then that matters of the mind had plunged to grave depths.

With these words Ellen began her second book, The Last Cheater’s Waltz: Beauty and Violence in the Desert Southwest, a book about the “geography of consequence.” At the end of this opening prologue, Ellen describes most clearly what she was questing for in life and writing. After fishing the lizard from her coffee and unfolding a Colorado Plateau map, she carries lizard, map and notebook to a sandy bench, and writes:

Beside a thick stand of rabbitbrush I spread out the big map and anchored its corners with stones…” “First I marked my present location with a small, shapely O. Next I reduced the Colorado Plateau to a manageable two hundred square miles or so around the home O. Then I outlined this perimeter on the map with a ring of fine red sand trickled from my fingers. A circle has no corners. So, to make my Map of the Known Universe portable, I transcribed all that fell inside the circle into sections and roughed them out on pages in the notebook, like an atlas.

As the sun rose higher, the cliffs shed their crimson light and turned flat and brassy. Tenderly, blue belly down so it would not sunburn, I placed the lizard on the map. The small corpse rested on our land—literally on the very dirt where my husband and I were soon to build our house—on the O, at the center of the circle.

It was time to get to know the neighborhood.

This, without doubt, is my favorite passage from Ellen’s writing; it is unexpected, funny and at the same time poignant and a clear manifesto of Ellen’s life and purpose. Ellen wrote four books about getting to know Bluff and her Four Courners neighborhood.

While the multi-award winning Anthropology of Turquoise is a tour de force, another of my favorites, Eating Stone is, to me, the most Ellen-like. The book reminds me of sitting atop a sandstone outcropping low over the San Juan River with Ellen, hearing what she’s been up to and laughing in the sun’s warmth. About camping in the desert with friends while tracking bighorn, Ellen writes,

Sunrise in the redrock desert has the calm of water. Strange that it be thus in a parched expanse of rock and sand. Yet this is how it comes: a spill of liquid silence, sunlight the color of embers, every surface bathed in it. The heart aches to live to see the start of a day, every day, luminous in the unmoored distance.

How can there be such quiet among a most garrulous species grouped together in space and task—no voices yet? I believe that the quiet prevails because all of us are desert people. We are known gazers into the horizon at early hours. That pause between social discourse and the solitude of the senses feels acute today…Perhaps the quiet is accidental prayer, an attentive stillness that conflates perception with desire. Maybe it is sleepiness at the early hour or the fact that some among our group are quite bashful. The low sun torches the buttes and mesas around us. Each saltbush stands distinctly silver-green on the cayenne red pediment, casting its own violet shadow. The light is what we watch, what steals our voices.

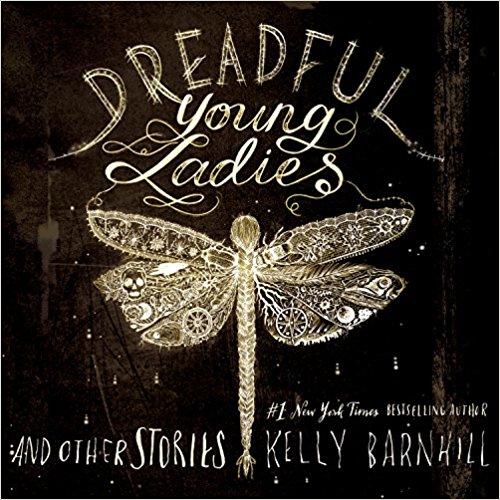

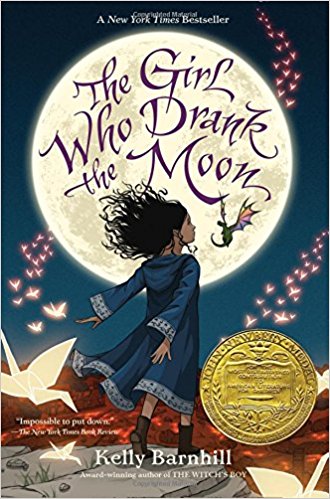

Kelly is an author, teacher and mom. She wrote THE GIRL WHO DRANK THE MOON, THE WITCH’S BOY, IRON HEARTED VIOLET, THE MOSTLY TRUE STORY OF JACK and many, many short stories. She won the World Fantasy Award for her novella, THE UNLICENSED MAGICIAN, a Parents Choice Gold Award for IRON HEARTED VIOLET, the Charlotte Huck Honor for THE GIRL WHO DRANK THE MOON, and has been a finalist for the Minnesota Book Award, the Andre Norton award and the PEN/USA literary prize. She was also a McKnight Artist’s Fellowship recipient in Children’s Literature.

Kelly is an author, teacher and mom. She wrote THE GIRL WHO DRANK THE MOON, THE WITCH’S BOY, IRON HEARTED VIOLET, THE MOSTLY TRUE STORY OF JACK and many, many short stories. She won the World Fantasy Award for her novella, THE UNLICENSED MAGICIAN, a Parents Choice Gold Award for IRON HEARTED VIOLET, the Charlotte Huck Honor for THE GIRL WHO DRANK THE MOON, and has been a finalist for the Minnesota Book Award, the Andre Norton award and the PEN/USA literary prize. She was also a McKnight Artist’s Fellowship recipient in Children’s Literature.